Cold Weather Rowing and Sculling

by Admin | Nov 18, 2012 | Articles |

Captained by Leander-based Jock Wishart, the Old Pulteney Row to the Pole six-man crew left Resolution Bay 29 July 2011. They sculled 450 miles across the Arctic Ocean, reaching magnetic North Pole after 28 days in constant daylight. The expedition was organised to highlight effects of climate change on Arctic ice. Air temperature during the challenge ranged from -2 to 6 degrees C. But actual air temperature, taking into account significant wind chill factors, was lower.

Crew member Billy Gammon made these blog comments:

‘In the Arctic, survival depends on your crew and on your kit. When it comes to choosing gear for extremely dry, cold conditions, a three-layer system is best. The first layer is a thermal layer designed to wick away moisture from your skin. The second layer is for warmth and the third keeps the wind out. We’ll also be taking essentials like a decent hat and sunglasses or goggles to protect our eyes from the glare from the sea and ice and a high factor sun-cream.’ (Excerpt from Row to the Pole blog pages)

The crew wore Henri Lloyd under clothing, headwear and boots on top of an Icebreaker/Finisterre base layer. They used Palm drysuits and cags (designed for kayaking) when resting on exposed ice flow or when intentionally immersing themselves in 1 degree C water (the Arctic Ocean resists surface freezing due to salinity and depth).

The voyage, which has been hypothetically possible each summer since 2008 as a result of ever decreasing polar ice cap, went well in the early stages, with surprisingly swift progress north. Beyond Thor Island, the crew was confronted with a two mile field of ice rubble. Any free flowing leads rapidly froze. Four crew members donned their dry suits and submitted themselves to an ocean swim involving two hours of “wading, whacking and winding their way through and over ice” to reach a wider lead.

For the final leg of their journey they detoured to follow leads which closed up behind them, rowing into strong northeasterly winds of 20+ knots. It took three hours to travel five miles, one hour to cover the last 100 metres. When the way was completely blocked, they dragged their 1.3 ton boat (designed with tow hooks and sledge-based hull) over ice hillocks and crumbling rubble.

This was the first polar rowing expedition since Antarctica 1916 when Sir Ernest Shackleton ordered his Endurance crew to their rowing boats to escape pack ice surrounding and crushing their ship.

Shackleton’s men lumbered with heavy kit and equipment in embalmingly cold conditions

Fortunately rowing and sculling in England does not involve these extremes, but cold weather can pose serious threats, requiring preparation and respect.

Perceiving Cold

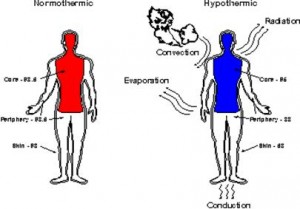

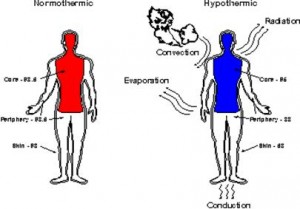

In his Outdoor Action Guide to Hypothermia and Cold Weather Injuries, Rick Curtis, Director of Princeton University’s Outdoor Action Program, explains and illustrates four ways that humans lose heat to the environment:

- Radiation occurs when ambient temperature is lower than body temperature

- Conduction relates to molecular transference of heat energy through direct contact. Water, because it is denser than air, conducts heat away from the body 25 times faster. As Curtis points out:

‘Generally conductive heat loss accounts for only about 2% of overall loss. However, with wet clothes this loss is increased 5x.’

- Convection encompasses conduction where one of the objects is in motion. Wind chill factor and water flow rate in contact with a human body both greatly accelerate heat loss, although water convection is more rapid than air convection, again due to density.

- Evaporation is heat lost converting water from liquid to gaseous state. Perspiration is a bodily response to eliminate excess heat. Normal respiration also involves evaporation. Air entering lungs is heated and then exhaled with an increased moisture content.

Rowing and sculling pose particular challenges in cold conditions. Athletes can have prolonged exposure to adverse weather while alternately perspiring heavily or resting (waiting at the start of a race or sitting inactive in safety position while other crew members row).

Perspiration causes blood vessels to dilate, shifting blood flow from body core to skin surface where nerve endings respond to temperature change (this same effect applies when drinking alcohol). This allows more blood flow past the skin surface, a natural means of eliminating excess heat. In cold conditions where there is a high windchill or in the event of capsizing in cold water, the danger of body heat loss is, therefore, enhanced for someone who has been sweating (or drinking alcohol).

Curtis differentiates between core body temperature (internal organs) and periphery temperature (appendages, skin and muscle). Whilst a periphery temperature drop can produce discomfort, core temperature is essential to basic metabolism and physical well-being.

Tom Davies (RRBC Mens’ Squad and retired polar medical consultant) offers further insight:

‘Discomfort enables people to avoid exposure which would be dangerous, so by and large, discomfort is protective. On a cold, windless day, if you are dry you will not lose much heat, the loss being mainly a result of conduction to surrounding air. Discomfort as a result of heat loss in low environmental temperatures is significantly increased by wind and water.’

‘If you are wet, heat loss accelerates, the speed depending on the cause. If you have fallen in, loss of heat by conduction to surrounding water is very fast; if the temperature is near freezing, you can lose so much heat that your life is endangered within a few minutes; blood cools and soon your vital organs – brain, heart and other muscles – will no longer function.’

‘If you are wet because of rain or sweat, heat loss is much slower, because there is no loss by conduction to surrounding fluid. However, there is loss from water evaporation on clothing, a process amplified by wind. Although slower, this loss can be just as dangerous as that caused by immersion.’

‘If you start to cool, the body reduces blood flow to the periphery (hands and feet, and to a lesser extent , the head) to slow heat loss. They go white, you feel pain and you lose dexterity; in extreme situations this can cause skin damage. It also increases fluid in the body core, which results in a need to pass urine. This is made worse by adrenaline, having a similar effect.’ ’

Hypothermia occurs when core body temperature is excessively compromised (35 degrees C or below), impairing normal muscular and cerebral functions.

Early symptoms include:

- stumbles, mumbles, fumbles, and grumbles which indicate changes in motor control *shivering and goose bumps

- confusion

- unable to perform simple tasks such as doing up a zipper or counting in sevens backwards from 100

- irrational behaviour

With all of this information in mind, here is a list of reasons why some rowers and scullers experience a heightened perception of cold:

- Dehydration- Fluid loss due to evaporation that is not adequately replenished

- Wet clothing- Increases conductive heat loss

- Alcohol consumption- Increases conductive heat loss

- Perspiration- Increases evaporation and conductive heat loss

- Inadequate nutrition- Reduces body’s disposable glycogen fuel reserves

- Excessive caffeine intake- As a diuretic, this increases fluid loss

- Tobacco/nicotine – A vasoconstrictor which increases the risk of frostbite

- Lack of fitness- Effects the efficiency of metabolism

- Thin or small people- Large surface area to volume ratio

- Minimal body fat- Less inherent insulation

- Inefficient body thermoregulation- More common in the elderly

- Medical conditions- Such as diabetes mellitus, which can affect metabolism if not well controlled

- Exhaustion- Due to overtraining or lack of sleep means body is less capable of maintaining warmth through activity or shivering

- Lack of concentration- Easily distracted by discomfort

Assessing Risk before an Outing

British Rowing National Water Safety Adviser, Clive Killick offered some helpful tips during last winter’s coldest period:

- Ice is an important indicator of extreme cold. It is a risk on land- slipping and dropping equipment and on the water- floating sheets of ice will damage boats.

- Cold water immersion is a high risk, particularly for juniors and masters. All athletes should read BR RowSafe guidance (Section 1.8), which deals with Cold Water Immersion and Hypothermia. (A copy of Row Safe is in the locker under the RRBC equipment logbook) The most important thing is to reduce the likelihood of a capsize.

- In very cold weather, there should be a much higher priority given to assessment, preparation and communication.

Specifically relating to Cambridge, Dan Wilkins, Honorary Secretary of CUCBC, has offered the following advice:

‘When there is substantial ice on the river (the guideline on the Cam is that the ice is more than 1mm thick more than 2m from the bank), crews should not boat. Ice poses a hazard to the hull as it can cut through the relatively thin and delicate composite material, in turn leading to swamping of the boat.’

- Swamping is when a boat fills with water.

Caroline Smith was cox of the Oxford University Lightweight Rowing Club’s VIII that was swamped during a winter training camp outing in Amposta, Spain on 29 December 2000. One of the crew, Leo Blockley, drowned. The boat had no underseat buoyancy aids, so could not support the crew weight when swamped.

Smith created a website to highlight this problem.

www.leoblockley.org.uk

Says Smith:

‘We can’t do anything about the weather, which is why it is imperative to have boats which will remain safe in any conditions which may be encountered…. The ultimate reason for sufficient inherent buoyancy is simply that the crew should never have to leave the boat in circumstances where it would be the safest place to stay- like a swamping incident in adverse weather conditions.’

Smith, Leo Blockley’s parents and others have been campaigning since Leo’s death for mandatory sufficient inherent buoyancy to be required in all boats under British Rowing jurisdiction. Currently BR only require that:

‘….All newly constructed boats must have sufficient inherent buoyancy, together with their oars and sculls, to support a seated crew of the stated design weight such that the rowers’ torsos remain out of the water and the boat can be manoeuvred.’ (RowSafe 2.3 Boats and Blades- Minimum Standards to be adopted)

But, as Stephen Blockley has pointed out, older boats make up a huge proportion of the national fleet and tend to be used by the more junior and less experienced crews. Currently only the North West region in England requires all boats to meet the quoted standard, including old boats, both for racing and for training outings.

- Should you scull alone? Many single scullers prefer early or mid-day outings when there may be less traffic. Mike Sullivan advises:

‘Be aware of temperatures and conditions. 100 degree rule should apply. 100 degree rule is that if air temperature plus water temperature is less than 100 degrees, I pay close attention to where and what I’m going to row, staying not only close to shore but generally closer to home. (100 degrees Fahrenheit is 37.7 degrees Celsius) Do not scull by yourself if water plus air temp is less than 100.’ (excerpt from Sullivan’s e-book Handling your Sculling Boat on Land and on Water, which can be purchased on the Rowperfect website)

http://www.rowperfect.co.uk/shop/handling-your-sculling-on-land-and-on-water.209.html

- Capsizing is a shock even when water is not very cold. The best outcome results from a clear, well-conceived plan prior to setting out.

-Decide what you will do if you capsize- try re-entry in situ, kick to the bank while hugging the boat hull to re-enter there or wait with your boat where you have capsized for assistance. The cold shock reaction on hitting water is disorienting and makes indecisiveness particularly dangerous.

-Research and practice before the outing. If you are going for re-entry, study British Rowing advice posters (These are displayed on the RRBC Safety Noticeboard) for correct procedures and try doing this first during a coached capsize drill. If you plan to kick yourself and the boat to the bank, learn the best way to drain a boat bankside and how to re-enter in less than ideal conditions.

-Re-assess your capsize plan before every outing. Very cold weather might mean you take a different approach than during a warm summer’s day.

- Communication– Who knows about your outing? Have you signed out the boat? And signed back in on returning?

Ongoing Risk Assessment

Light aircraft pilots are trained to constantly reassess risk as they fly. Not only are they steering the aeroplane, maintaining height, spotting for other airborne craft and high landmarks, liaising with air traffic control, navigating, etc. but a good pilot will always know which field he would aim to land on in the event of an engine failure or rapidly deteriorating conditions.

Changing river conditions mean that rowers also need to keep their risk assessment active throughout an outing.

- Abandonning or Shortening an Outing

Cold weather can often be accompanied by poor visibility. Boat lights are important if visibility is limited. If conditions deteriorate (precipitation, strong wind, etc) and you are ill-equipped or not experienced enough to cope, consider cutting short your outing.

Tom Davies advises:

‘If you fall into very cold water, get out as soon as possible, even if the air feels colder.’ Change into or add on dry layers of clothing if you have any in the boat. If you begin to shiver, it’s time to head back.

Most importantly, when conditions feel very cold, remember to monitor your own mental capability as well as that of your crew. Even people suffering from mild hypothermia can make poor decisions that lead them into trouble.

Jerky movements are an early sign. One of the first effects of hypothermia is loss of hand dexterity. Can you touch your littlest finger to your thumb? With your blades in safety position, can you do the Incy, Wincy Spider movements with your hands? Can you confidently recite your mobile phone number backwards? Be aware of a crew member who becomes reticent to talk when addressed or who loses concentration and rows badly.

Kit

This advice has been adapted to apply to rowing from the Ice Bike website:

If you step outside and are immediately cold, (not on the face, but on the torso, under your shirt), you are dressed too lightly and will probably not warm up, even with exertion.

If you are mildly chilly you will soon feel comfortable. Don’t push too hard at first. Warm up before you really start cranking.

If you feelwarm while taking your equipment waterside, you are overdressed for the outing.

In The Art of Sculling, Joe Paduda says:

‘Dress warmly but in layers so you can strip down as you warm up. Your outer layer should be easy to remove.’

Paduda advises against

‘…Traditional rowing jackets made of nylon or other “waterproof” materials because they rarely are completely waterproof and they retain a lot of moisture. Since you heat up quickly and put out a lot of sweat while sculling, they really don’t seem to serve much of a purpose. You won’t wear this type of jacket much beyond the warm-up or you will be swimming in sweat before the first piece is over. If you are wearing such a jacket for warmth, you might be better off with something that gives you protection from the wind yet breathes.’

‘A light nylon windbreaker that’s been treated with a water-repellent coating keeps most of the backsplash off you and will even keep you dry in a light rain. It also breathes very well. Make sure you find one that gives you lots of mobility and covers your arms and wrists even when you are fully compressed at the catch. Also, make sure the tail isn’t too long or it will get caught in the slide.’

‘In practice,’ Tom Davies suggests, ‘Comfort is a good guide. For normal outings and before/between races, you should reduce your cover to a level at which you are on the cool side of comfortable; this gives sweat a chance to evaporate. If you stop, you should replace the outer layer even if the under layers are not completely dry. If it is raining your should keep your outer layer on.’

On periphery kit, Davies says:

‘Many people prefer a woolen hat though I prefer a waterproof but breathable one. Comfort and dexterity are the major concerns for hands as their contribution to heat loss is small. Pogies are good, but they do hamper dexterity a bit and as you warm up, sweat does condense on the inside. Many people prefer to have cold hands as eventually blood vessels will open and you hands will warm up. With feet, comfort is the main concern. More than one pair of socks does help, and if it is wet, waterproof socks are excellent.’

Paduda prefers removing pogies to race but says that they ‘will prevent that awful pain in the hands that comes when you thaw out after an initial freeze.’

‘The most challenging conditions I encounter in my sculling coaching,’ explains Robs Juniors Coach Pete Shiels, ‘is when it is just above freezing and windy or raining or both. In these conditions, for a novice sculler, things are most likely to go wrong. If an athlete turns up to train in a non-wicking type of cotton t-shirt, this is an added disadvantage. And jeans are an absolute no-go.’

Claire Allen (Robs Womens’ Squad and polar scientist) offers this advice on kit:

‘Cold weather rowing… Layers, layers and more layers! Double the amount of kit you think that you need – especially if small boats are involved! If you don’t have pogies or don’t trust to wear them, then wear mittens (much warmer than gloves) until you are ready to row and put them on again when marshalling or pausing.’ ‘No matter how cold your hands or feet get during an outing don’t put them close to a heat source or into hot water until you can feel them properly otherwise you risk getting chill blains.’

RRBC WJ15 athlete Amy Bland also recommends layering:

‘Long-sleeved top, t-shirt then body warmer and sun hat, plus pogies in the boat.’

With a reputation for always being prepared, Bland’s race day kit list includes :

- Clean top and pair of socks for each division racing

- Raincoat, as then it won’t rain

- gloves for bankside and pogies for in the boat

- woolly hat and sunhat (anticipating weather changes)

- jumper/fleece

- wellies, trainers and flip-flops

- lots of water

- flask of hot drink

- homemade flapjacks

Dan Wilkins of CUCBC advises crews to bring extra layers, kept in a plastic bag to keep them dry in the boat, or to be carried by coaches on the bank.

Hints

- In The Art of Sculling, Joe Paduda suggests keeping oars in a warm area.

‘The reason cold-weather sculling is so hard on the hands is your hand has to warm up the oar handle before it can stay warm itself…’

- If you are forced to spend a substantial amount of time in very cold water, try not to move. When swimming or treading water, rate of heat loss increases by 40%. This is because limb activity draws warm blood (therefore heat) away from the core into limb muscles. Agitating movements force the body to continually warm constantly changing displaced water, thereby sapping away more precious warmth.

- Instead of pogies cut holes in woolen socks. Cheaper and more hip, suggests one American website.

- Example of some American extreme cold water immersion tests

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J1xohI3B4Uc

- There has been much conflicting research on body heat loss via an uncovered head. Dr. Gordon Giesbrecht (also known as Professor Popsicle) and Dr. Murray Hamlet explain (Wilderness Medicine Newsletter 2007/02/14) that in normal conditions head heat loss amounts to around 7% of total body heat loss. With exercise, this increases, along with cerebral blood flow, to around 50%. However, with continued exertion, blood flow is increasingly redirected to skin so that normal body core temperature can be maintained. Once sweating begins, heat loss through the head returns to around 7% of total heat loss.

In wet conditions (immersion or heavy precipitation), heat loss via the head increases significantly, so the best, consistent advice is to wear a suitable hat for outings in cold weather. Also note that a shivering hypothermic victim can lose around 55% of total body heat through the head; treatment, therefore, should include a dry hat for the victim if possible.

- Marin County Sheriff’s Department Search and Rescue Team is a mountain rescue Type 1 certified team (equipped to be self-sustaining for 60 hours in all environments) Their motto is Anytime, Anywhere, Any Weather. On their website, Michael St. John points out:

‘Good food and water intake (are) more important than equipment. Your body needs food and water to generate heat and handle exertion. Eating well and staying hydrated is the best way to prevent hypothermia.’

- And some final advice from Professor Popsicle on hair as a means of retaining warmth during outdoor pursuits:

‘In order for hair or fur to provide a protective thermal barrier, it has to be much denser than what we humans grow and it has to be in layers of different types of fur to provide a thermal barrier. Beards are great, but they do not keep you any warmer. And bald is beautiful.’

Comments and feedback to:

Donna McLuskie

Communications Officer

Rob Roy Boat Club

communications@robroyboatclub.org.uk

Donna McLuskie has asserted her rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1998, to be identified as the author of this work. Contributions from Rob Roy Boat Club members and other sources as cited. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without prior permission.

Recent Comments